You have heard me mention Peter Lynch in previous articles. Lynch, a value-investor who ran Fidelity’s Magellan Fund, averaged a 29% annual return between 1977-1990. In other words, if you had invested $1k in Lynch’s fund in 1977, it would have grown to $43k by 1990. Lynch’s return was stellar, but the real question is: “How did his investors do?”

The answer is quite surprising. Lynch calculated that the average investor in his fund made only 7% per year between 1977 and 1990. For this average investor, $1k only grew to $2.5k! How could this be? Where did all their money go?

Lynch explained it this way: When his fund had a setback, money would flow out of the fund through redemptions. Once the fund’s performance improved, money would pile back into the fund, having missed the recovery. Investors bought high and sold low, and it cost them dearly.

What Lynch’s investors did to themselves seems so strange that it must be a fluke. But in reality, the evidence indicates that when an investor looks in the mirror, he sees the worst enemy of his investing success: himself.

My friend Eric Falkenstein examines the actual returns that investors achieve in his book, The Missing Risk Premium. Over the long haul, the US stock market has had an inflation-adjusted return of about 6-7% per year. Yet, through mistiming the market and paying transaction costs, the average investor drops that 6-7% per year return all the way down to a 2-3% per year return, or just 0-1% per year after paying taxes. Ouch!

Which investors do better? Once again, the answer may surprise you. According to an internal Fidelity study of client accounts between 2003-2012, the best-performing accounts belonged to customers who forgot they had their Fidelity accounts.

Do institutional investors, who command huge research budgets and an army of analysts, perform better than individuals? Unfortunately not. A 2009 study in the Financial Analysts Journal analyzed 80,000 institutional investment decisions between 1984-2007. The study concluded that the investment products receiving new contributions underperformed products experiencing withdrawals over the following one, three, and five years.

Joel Greenblatt, another well-known value investor with a 40% annual return, discussed a similar phenomenon in his book, The Big Secret. Greenblatt studied which managers performed in the top 25% for 2000-2010. For those managers with the best record over the decade:

97% spent at least 3 out of 10 years in the bottom 50% of performance.

79% spent at least 3 out of 10 years in the bottom 25% of performance.

47% spent at least 3 out of 10 years in the bottom 10% of performance.

When asked about the study, Greenblatt said:

“You’re pretty sure that none of their clients actually stuck with them to get the good returns. And to beat the market you have to do something [a] little different than the market. You’ve gotta zig and zag a little differently. But clients are not very patient.”

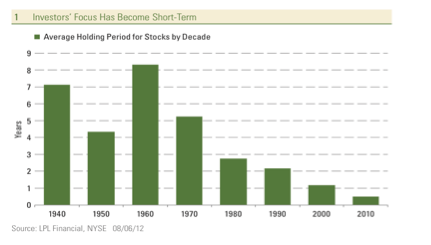

In the studies discussed above, investors shared two common errors: first, being impatient; and second, buying high and selling low. It is easy to identify whether or not we are patient investors -- just look at your turnover or your average holding period (see the graph above). What is harder to understand is why investors so often buy high and sell low -- a behavioral phenomenon that is both irrational and counterproductive. Perhaps the simplest way to explain this phenomenon is to consider the two ways that humans tend to make purchasing decisions, epitomized by how we buy chicken vs. how we buy perfume.

How do you buy chicken? When my wife goes to the grocery store, she will purchase chicken if it is below an acceptable price -- in our area, $3.00/lb for chicken breast. If the price is above this acceptable threshold, the Kent household will dine on turkey, beef, pork, or vegetables. On the other hand, if chicken is on sale, Brooke backs up the Mazda and fills the garage freezer. Brooke understands the economic value of chicken relative to the alternatives. As the price goes down, the quantity we purchase goes up.

How you buy perfume is an entirely different beast. Having been gifted with both an X and a Y chromosome, I have zero ability to differentiate between good and bad perfumes. Lengthy discussions with a perfumer add nothing to my understanding. As a result, if I’m buying perfume, I buy an expensive bottle, because if it costs more, it must be better, right? Most consumers apply a similar rationale to watches: a Cartier must be better than a Timex because it costs more, right? (But does it tell time any better?) With luxury goods, consumers invert their normal demand response. As the price goes up, we assume the product is more desirable, and we purchase more. Conversely, as the price goes down, we assume the product is less desirable, and we purchase less. Strange but true.

Given the two ways that people tend to make buying decisions -- chicken vs. perfume -- which method do people tend to use when buying stocks? Suppose a stock goes “on sale,” and its price decreases. Do investors stampede to the exchanges to buy more? Or, suppose a stock’s price increases. Do investors rush to sell? In my observation, the vast majority of investors purchase stocks -- or other investments -- exactly like they purchase perfume or luxury goods. The more the price increases, the more they want to buy. The more the price decreases, the more they want to sell. However, as the studies above have shown, such behavior is quite expensive, and it costs investors a huge price in their lifetime returns. In contrast, a value-investing approach, like ours, forces investors to view stocks the same way we view chicken. This mindset gives value investors an advantage over the herd.

As food for thought, do you think of stocks as chicken or perfume?

David R. “Chip” Kent IV, PhD

Portfolio Manager / General Partner

Cecropia Capital

Twitter: @chip_kent

Nothing contained in this article constitutes tax, legal or investment advice, nor does it constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security or other financial instrument. Such offer may be made only by private placement memorandum or prospectus.