I’ll begin this article with two quotes by Peter Lynch. Lynch, a value-investor who ran Fidelity’s Magellan Fund, averaged a 29% annual return between 1977-1990.

“The key organ for the stock market is not the brain, but the stomach.

I can’t recall ever once having seen the name of a market timer on Forbes’ annual list of the richest people in the world. If it were truly possible to predict corrections, you’d think somebody would have made billions by doing it.”

This quarter, the overall market experienced a correction of more than 10% within 5 trading days -- “correction” being industry jargon for losing a lot of money very quickly. We haven’t experienced such a move for a few years, but during the last 115 years, investors experienced on average:

-5% market correction: 3x / year

-10% market correction: 1x / year

-20% market correction: 1x / 3.5 years

-30% market correction: 1x / 8 years

Such fluctuations are a fact of life in equity investment. The last few years of tranquility were unusual, while, in fact, the recent fluctuation was very usual. Since market fluctuations are much larger than fluctuations in the economics of the underlying businesses, these market fluctuations present opportunities for value investors. Although unnerving, such volatility is our friend.

The other fact of life is that human beings are emotional animals. We crave certainty, especially in financial markets, where such certainty cannot possibly exist. Psychologically, we are programmed to panic at wild market swings. Dealing with market swings rationally is a learned response.

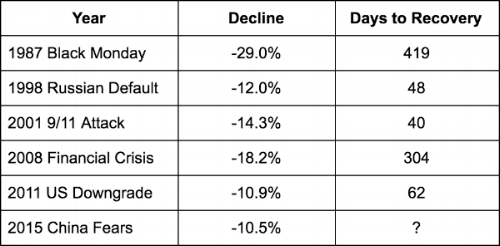

A market loss of 10% in only five trading days is unusual. Since 1976, there have been only six times where the market has fallen 10% or more in five trading days:

The recovery time for the previous declines was relatively short. Even in the 1987 case, which appears long, the market ended up for the year.

Going forward, I expect precipitous drops to become much more common than what we’ve seen before. Over the last two decades, computers have taken over the operation of the markets. As I discussed in a previous article, “The High Cost of High Frequency Trading,” these computers are very dumb. The computers know the price of everything and the value of nothing. As a result, markets appear to be well-functioning and liquid -- until they are not.

Real-time financial media has enabled financial panic to spread faster than ever before, while internet trading, cell phone trading, and algorithmic trading have allowed that panic to be acted upon with unprecedented speed. For example, during the recent correction, “investors” were willing to pay almost 5% of their portfolio to insure against losses over the next 30 days! That is panic.

Fear of loss drives a lot of investor behavior and leads people to make short-term and irrational decisions in order to ease their fear of loss. Suddenly, self-professed long-term investors are unable to control their fear of loss and decide that the only sensible thing to do is become a “market timer.” These decisions will hurt their long-term return outcomes and provide opportunity for those who are prepared to focus their energies on the things that count and that can be controlled.

“Emotion is one of the investor’s greatest enemies. Fear makes it hard to remain optimistic about holdings whose prices are plummeting, just as envy makes it hard to refrain from buying the appreciating assets that everyone else is enjoying owning. Superior investors may not be insulated, but they manage to act as if they are. ”

Market corrections always raise the question of hedging. Running a hedged portfolio at all times is obvious, right? Not quite. What’s clear to the broad consensus of investors is almost always wrong. When the costs of hedging are considered, hedging is much less attractive -- at least in the current market.

“Far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, or trying to anticipate corrections, than has been lost in corrections themselves. ”

An investor could hedge by (1) shorting a broad market index, (2) buying puts on a broad market index, or (3) shorting a basket of the most toxic stocks he can find. Currently the S&P 500 is cheap relative to bonds. If an investor shorts the S&P or buys puts on the S&P, and bond yields stay low, he will likely lose money on the hege. Bond yields would have to rise above 5% -- which I think is unlikely -- or the market would need to appreciate significantly before shorting the index would seem like a good idea. Similarly, shorting a basket of terrible businesses tends to cost a few percent per year. And don’t forget that toxic sludge went up 20%-50% in the last 12 months.

In the current environment, I estimate that each of the three hedging strategies would cost on the order of 5%/year. While a smoother ride would be nice, I personally don’t think it is worth the cost. I would prefer a lumpy 15% return instead of a smooth 10% return -- the 5%/year drag would end up costing 66% over 10 years.

Having said that, there are situations where an investor could make money on a hedge. For example, in both 1987 and 2000, stocks were very expensive relative to bonds, so hedging stock exposure would have made sense.

Most long/short hedge funds have significantly underperformed since 2009 because they insisted on running short positions even though the market was historically undervalued. While I’m certain the smooth performance of these funds made them easy to sell to prospective investors after the preceding tumultuous years, being market-neutral ended up costing those investors a lot of money.

David R. “Chip” Kent IV, PhD

Portfolio Manager / General Partner

Cecropia Capital

Twitter: @chip_kent

Nothing contained in this article constitutes tax, legal or investment advice, nor does it constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security or other financial instrument. Such offer may be made only by private placement memorandum or prospectus.